Most of us have a fairly good idea that brains of Buddhist monks function far beyond most humans’ capabilities and that the monks can actually rewire their brains. While there is no question that Buddhist monks possess superhuman powers, how they do some really incredible out-of-this-world kind of stuff continues to fascinate and show scientists what we – ‘normal human beings’ – can all do.

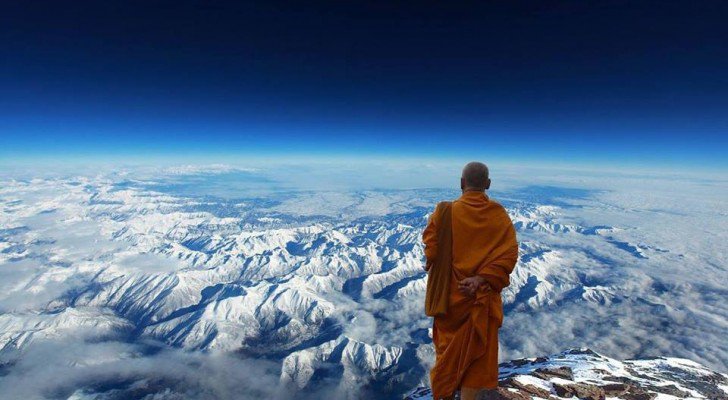

Professor Herbert Benson and his team of researchers from the Harvard School Of Medicine went to remote monasteries in the Himalayan mountains in the 1980′s to discover, decode, and document the subtle ways through which the monks manipulate their bodies – like raising the temperatures of their fingers and toes by as much as 17 degrees, and lowering their body’s metabolic rate by up to 64% – using a stress reduction yoga technique called ‘g Tum-mo’.

The Harvard research team also recorded monks drying cold, wet sheets with body heat. They also documented monks spending a winter night – when temperatures reached zero degrees F – on a rocky ledge 15,000 feet high in the Himalayas — wearing only woolen or cotton shawls. These remarkable feats, the Harvard research team observed, were achieved by intense daily meditations, guided exercises and spiritual conditioning. They noted:

“In a monastery in northern India, thinly clad Tibetan monks sat quietly in a room where the temperature was a chilly 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Using a yoga technique known as g Tum-mo, they entered a state of deep meditation. Other monks soaked 3-by-6-foot sheets in cold water (49 degrees) and placed them over the meditators’ shoulders.

“For untrained people, such frigid wrappings would produce uncontrolled shivering. If body temperatures continue to drop under these conditions, death can result. But it was not long before steam began rising from the sheets. As a result of body heat produced by the monks during meditation, the sheets dried in about an hour.”

Based on his experiments and experience, Benson stressed that a better understanding of advanced mediation could lead to better treatments for stress-related illnesses. He noted:

“More than 60 percent of visits to physicians in the United States are due to stress-related problems, most of which are poorly treated by drugs, surgery, or other medical procedures. If such an easy-to-master practice can bring about the remarkable changes we observe, I want to investigate what advanced forms of meditation can do to help the mind control physical processes once thought to be uncontrollable.

“My hope is that self-care will stand equal with medical drugs, surgery, and other therapies that are now used to alleviate mental and physical suffering. Along with nutrition and exercise, mind/body approaches can be part of self-care practices that could save millions of dollars annually in medical costs.”

In 2011, Zoran Josipovic, a research scientist and adjunct professor at New York University and a Buddhist monk himself, placed the minds and bodies of prominent Buddhist monks into functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machines to track the blood flow to their brains while they were meditating. Josipovic told BBC:

“The brain appears to be organized into two networks: the extrinsic network and the intrinsic, or default, network. The extrinsic portion of the brain becomes active when individuals are focused on external tasks, like playing sports or pouring a cup of coffee. The default network churns when people reflect on matters that involve themselves and their emotions. But the networks are rarely fully active at the same time. And like a seesaw, when one rises, the other one dips down. This neural set-up allows individuals to concentrate more easily on one task at any given time, without being consumed by distractions like daydreaming.

“[But] Some Buddhist monks and other experienced meditators have the ability to keep both neural networks active at the same time during meditation – that is to say, they have found a way to lift both sides of the seesaw simultaneously. This ability to churn both the internal and external networks in the brain concurrently may lead the monks to experience a harmonious feeling of oneness with their environment.”

In 2008, neuroscientist Richard J. Davidson conducted a research on Tibetan Buddhist monks at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to find out how meditation makes Buddhist monks’ brains superhuman. He discovered that “over the course of meditating for tens of thousands of hours, the long-term practitioners could dramatically increase neuroplasticity and had actually altered the structure and function of their brains”.